Dear We Are Teachers,

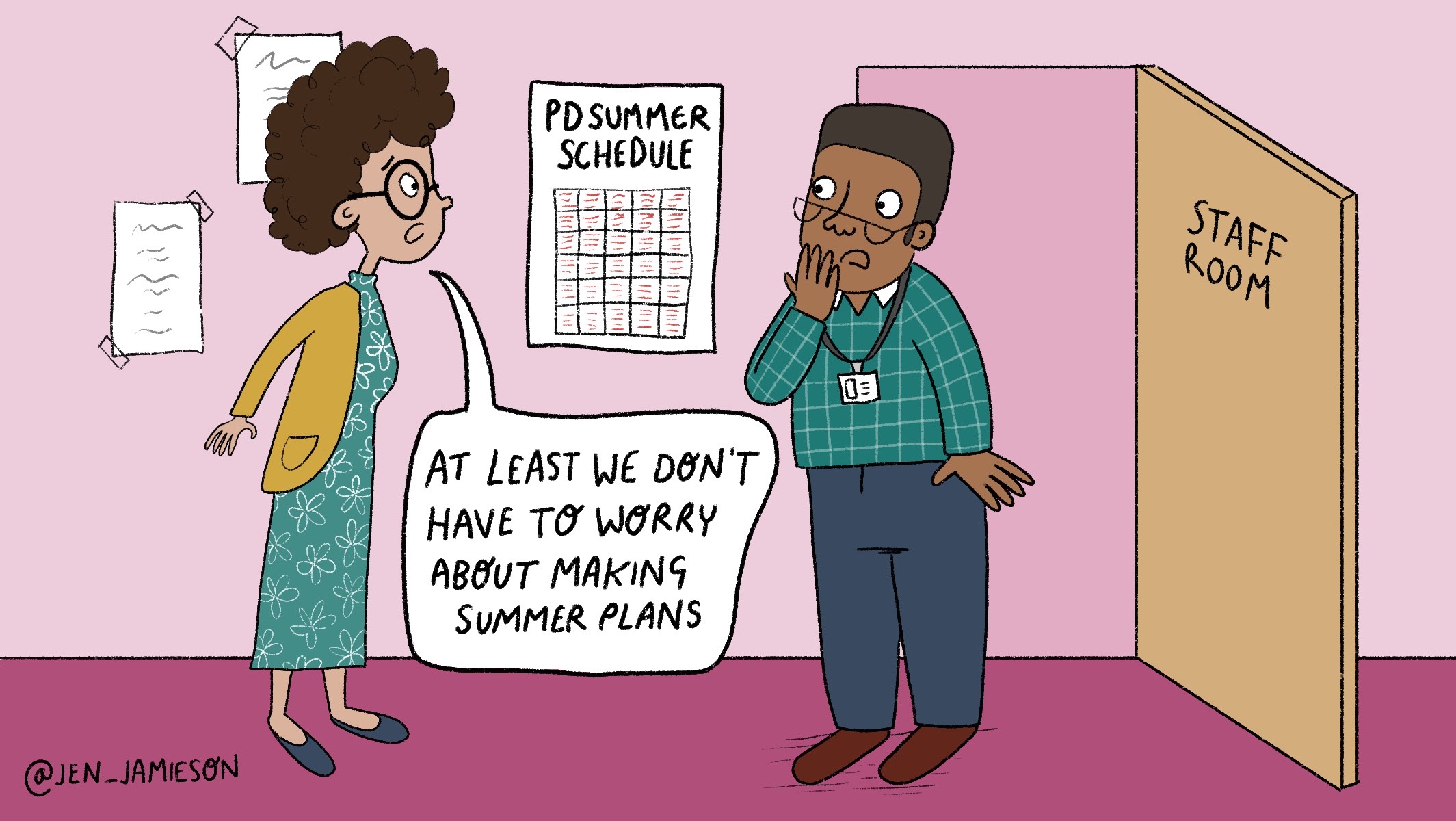

Summer is less than a month away, and my principal just announced that he expects our entire ELA team to do four weeks of training in July. His email specifically said this training isn’t optional. But how can he require that with such late notice? I don’t have plans—I just don’t want to spend half of my summer in PD! What should I do?

—PD-Swamped Summer

Dear P.D.S.S.,

There are very few things I am hard-lined about, but a teacher’s right to their time and peace is one of those things. This message would raise my eyebrows all the way to the heavens.

Your response is primarily based on your teaching situation. This situation is similar to a message we received a few months ago, and I’ll pull from there:

“If you are at a public school, contact your union representative. It’s possible that what you’re describing violates union contracts in some way. If it violates the agreement, the union can support you in making your best move forward. Alternatively, should the union say it’s allowable, a representative should explain that to you.”

“If a union does not protect you, you’ll need to look at your contract. You want to look for language about ‘mandatory activities’ or ‘outside normal working hours’ that may exist. If that’s present, your school may be within your contract.”

So, if you’re in a union, I strongly recommend reaching out to them ASAP.

If you’re not in a union, and your contract does not support this kind of work, I would calmly and respectfully tell your administration that, while you’d like to attend the training, you have already made other plans during your contractually mandated breaks. Be as kind and gracious as possible, and say you will happily find another way to participate in training at another time. If they continue to push, you need to decide how far you’d like to take the situation (i.e., higher up the administrative chain, legal representation, or finding a new school).

If your contract doesn’t protect you, you have, unfortunately, fewer options. You could try noting how late the request is and saying you have other plans already in place. You could also try to get compensation for the time you’ll spend in the PD, since it’s taking up a considerable amount of your time in the summer.

Overall, though, this situation sounds incredibly frustrating. I hope there is a good resolution. Good luck, and I believe in you!

Dear We Are Teachers,

I’ve been teaching for 30 years and usually have solid classroom management, but this group is tough. The principal and counselor have started offering rewards (mostly candy) to a few students if they behave for a set amount of time. I’ve already explained to both the kids and the adults why I think food rewards are a bad idea—unhealthy habits, extrinsic motivation, and the fact that we don’t train kids like dogs. How can I communicate my concerns firmly but diplomatically?

—They’re Kids, Not Dogs

Dear T.K.N.D.,

Oomph. I appreciate your honesty and deeply understand your reservations. The intentions might be good; I have memories of catching a Jolly Rancher from a math teacher after finally getting something right. Candy or extrinsic motivators, on occasion, aren’t inherently bad.

However, as you point out, a larger culture created by these suggestions, like candy to presumably “misbehaved” students, can be problematic. I spoke with Alex Venet, an education researcher, writer, and consultant who founded Unconditional Learning, who noted that, “extrinsic motivators like this actually undermine intrinsic motivation. They don’t work to get to the bottom of the problem.” The reward is just a Band-Aid covering a real issue.

Venet also noted that these reward systems can create unhealthy relationships between students and food or students and teachers. The unspoken messaging is that food or acceptance is tied to obedience. We’re not looking for students to be mindlessly obedient—we want them to be compassionate and motivated members of our class community.

One recommendation is to come to the table with solutions: “Sometimes the best way to disrupt these cycles is to name them,” Venet noted. “Say, ‘Hey, I want to try something else. Let’s experiment with a new energy or new direction.’” To that end, is there another teacher you could visit who might have great relationships with these students? Having another teacher to lean on and learn from can help generate some new ideas that align better with your values.

Venet noted that coming up with solutions helps because it’s hard to get people to change a deeply entrenched belief, particularly if they don’t seem open to that change. That said, if you want to, you could present evidence (some examples here and here). While you don’t want to be rude, you also want stand up for what you know is right for your students.

Good luck, and I believe in you!

Dear We Are Teachers,

I’m a veteran teacher who was out of the classroom for a while (though still in education) and now in my third year as a middle school teacher. While I truly love it, I’m feeling judged by a few team members. One second-year teacher in another subject keeps turning vulnerable conversations into coaching sessions, even though her own teaching is mostly packets while she sits behind her desk. I’m all for growing and improving, but this feels weird. I’m also not about to run to the principal—I’m not a snitch. Is this kind of judgment from younger teachers normal now, or is something else going on?

—Don’t Coach Me

Dear D.C.M.,

Congrats on returning to the classroom! This situation presents an interesting dynamic. Personally, I can’t imagine ever trying to coach a veteran teacher without being asked explicitly for resources, particularly those first few years in the classroom. So, I understand why that doesn’t feel great.

There are a few options here. One is to approach it head-on. The next time the teacher starts to coach you and you’re not interested, you could kindly say, “Hey, thanks for sharing that. I’m actually not looking for coaching right now. I just wanted to share how I was feeling.” If they push back, you can continue to hold your boundary: “I appreciate you want to share. I’m not looking for that kind of conversation right now. Thanks!” and then you can leave.

This boundary— asking for the kind of support you actually need—is a really important one. My husband is also in education, and I will sometimes start a conversation by saying, “Can you listen instead of giving me feedback?” While it can feel uncomfortable at first, we both feel it’s much better than being resentful of his good intentions. I think that could apply here.

Another option is to share your thoughts with someone else. I understand you don’t want to go to the principal. Is there another trusted mentor teacher that your colleague looks up to? If so, you could gently share the feedback with them. I hope it helps to hear it from a trusted source.

Finally, you could steer clear of this teacher as much as possible. It sounds like they don’t yet have the skills to give you helpful support. They may someday, but until then, you can also save conversations that are a bit more vulnerable for someone you trust.

Overall, teaching is challenging, and I hope you find someone who can validate and support you! Good luck, and I believe in you!

Do you have a burning question? Email us at askweareteachers@weareteachers.com.

Dear We Are Teachers,

I’m in my 8th year of teaching high school, and this year in particular has weighed on me so heavily. I need tangible tips and tricks to see me through to the end of the school year. Not heady things like “remember your ‘why’” or “look for the positives,” but action items I can do (ideally based on research) to de-stress, reenergize, and thrive my way to summer. Any ideas?

—Desperately Seeking Motivation