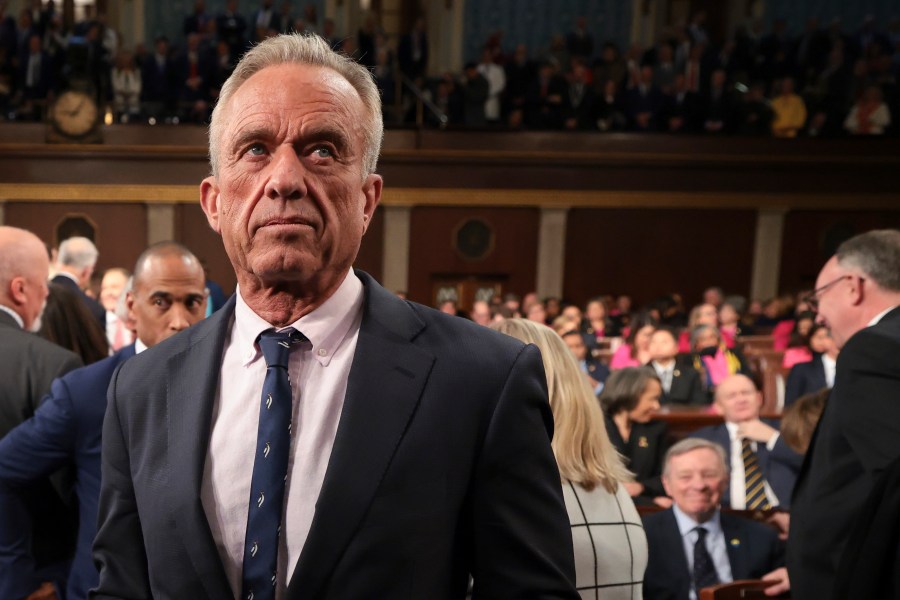

Health and Human Service Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s rhetoric on Texas’s measles outbreak is concerning physicians, who fear his public guidance is misguided and verges on being dangerous as he promotes vitamins and steroids as ways of treating infections.

The Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS) says 159 measles cases have been identified, including one unvaccinated child who died last week shortly after being hospitalized.

Only five of the infected individuals are confirmed to have been vaccinated against measles. Physicians in the state have urged that parents isolate their children and ensure that all members of their household have received a measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine to mitigate the spread.

About 80 percent of the measles cases in Texas have been found in children.

Kennedy has long questioned the safety and efficacy of vaccines, particularly the MMR vaccine.

In the face of the outbreak, he seemingly softened his stance, writing in an op-ed for Fox News that the vaccines “not only protect individual children from measles, but also contribute to community immunity,” though he maintained that getting immunized should be a personal choice.

At the same time, Kennedy has begun promoting the use of vitamin A, cod liver oil and the steroid budesonide as a way of treating measles, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updating its guidance on measles management to include “physician-administered outpatient vitamin A.”

There are no antivirals specifically indicated for measles. Most cases will resolve on their own rest at home. People who are hospitalized for measles receive supportive care until they recover.

HHS did not respond to a request for comment on Kennedy’s promotion of vitamin A, cod liver oil and budesonide for treating measles.

The case for vitamin A

Kennedy’s encouragement of vitamin A for children with measles is not entirely unfounded. It has long been observed that a vitamin A deficiency coupled with a measles infection can be devastating for a child.

“We know with some certainty is that in settings where a lot of children have vitamin A deficiency, giving vitamin A to children with measles saves lives, prevents complications,” Andy Pavia, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Utah, told The Hill.

But without a vitamin A deficiency, that prescription may not help someone with measles.

According to Susan McLellan, professor in the infectious disease division at the University of Texas Medical Branch, there is “no evidence that vitamin A supplementation improves the outcome of measles in a child who has no vitamin A deficiency in the United States.”

“The relative protective efficacy of vitamin A relative to immunization is minuscule in a non-vitamin A deficient population,” McLellan added.

Pavia also expressed concerns that Kennedy is misrepresenting what added vitamins can do for a measles patient.

“What Mr. Kennedy has suggested is that vitamin A is a treatment that will prevent the complications of measles, and we don’t think that’s very likely in the U.S. to make any difference,” said Pavia.

“He also intimates that it will be a preventive therapy, and there’s absolutely no evidence that taking extra vitamin A will prevent you from getting measles, only vaccines will do that or having had a previous infection.”

The updated CDC guidance advises that vitamin A should be administered “immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day for a total of 2 doses.”

In his op-ed, Kennedy pointed to a 2010 analysis that found a 62 percent reduction in measles mortality following two doses of vitamin A.

Several of the studies cited in the analysis focused on countries in Africa where vitamin A-deficient populations are more prevalent such as Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau and South Africa.

Riskier recommendations

In a Fox News interview on Tuesday, Kennedy said, “They’re getting very, very good results, they report from budesonide, which is a steroid. It’s a 30-year-old steroid, and clarithromycin and also cod liver oil, which has high concentrations of vitamin A and vitamin D.”

Pavia said taking cod liver while infected with measles “won’t hurt,” but pushed back on Kennedy’s apparent endorsement of budesonide and clarithromycin for treating measles, saying these drugs carry little benefit while adding unneeded risks.

“Not only is that not based on any science or good rationales, any good reason that it might work, but it’s potentially dangerous,” said Pavia.

One of the greatest problems with measles is that after you recover, you have suffered damage to your immune system, what we call immune amnesia, because the destruction of some of the memory lymphocytes that help protect you against future infection” Pavia continued. “So, giving steroids is only further going to reduce your immune ability to fight future infections.”

The Hill has reached out to the TDSHS for confirmation on whether budesonide is being deployed to treat measles patients in Texas.

When it comes to clarithromycin, Pavia noted one of the potential side effects is “a fair bit of GI distress” without offering any added benefits for treating the virus.

What physicians want the public to know

McLellan is one of a minority of physicians today who can say they encountered a debilitating measles outbreak, having been a practicing physician in Los Angeles when the city suffered one of the worst measles outbreaks in its history with more than 16,000 reported cases and 75 deaths.

Like other physicians, McLellan emphasizes the critical need for a full two-dose administration of MMR vaccines and pushed back on the notion that one dose is sufficient.

“People keep talking about, ‘Oh, your first dose gets you 90 percent protected, and the second dose gets you 98 percent.’ That’s not the way that it works,” McLellan said. “When one gets a dose of MMR vaccine, especially in the early childhood age, one in 10 doesn’t respond well.”

“That’s why a second dose is required to consider somebody fully immunized, because when they get their second dose, the chances that they’re fully protected now go up to 97 to 98 percent,” she added.

In Pavia’s view, the situation in Texas has “slipped our ability to easily contain it”

“We talk about outbreaks kind of slipping containment as happened with Ebola in West Africa. At a certain point it becomes so large that containment becomes extraordinarily difficult. I think we’ve hit that point with measles in Texas,” he said.

While most coverage has focused on children, Pavia also noted that unvaccinated adults who have never been infected with measles before are also at risk of developing a severe disease, adding that it can cause miscarriage and early labor in expecting mothers.

When asked how she feels to witness a measles outbreak of this level decades after it was considered eradicated in the U.S., McLellan said, “It absolutely breaks my heart.”

“My heart breaks for the child who died and for their family,” she said. “I also recognize that this is again one of those things where it is sad to see, perhaps a decreased amount of community, feelings of community support where what I do helps you.”