Immediately after the January 6, 2021 riot by Donald Trump’s supporters at the Capitol, the idea that Trump might be inaugurated as president for a second term was practically unthinkable. But the conditions that enabled his return to power have been decades in the making, beginning with policies first introduced by President Ronald Reagan.

After the tear gas dispersed and the Capitol was cleared up in January 2021, the FBI launched the largest federal investigation in U.S. history to arrest those accountable. Trump, who had urged protesters to “fight like hell,” would later face a federal indictment for his role in the chaos. Surely, this would make any new presidential campaign seem laughable.

So, how on earth did Trump win?

Commentators were quick to blame the Democrats’ time in office. Did President Joe Biden turn his back on the working class? Yes, he did, but that doesn’t explain why almost all voting groups shifted toward Trump, who in his first term became the first president since the Great Depression to leave office with fewer jobs in the country than when he entered.

Some argue that Biden dropped out of the race too late. But he was trailing in the polls even before his disastrous debate appearance. Others say that Kamala Harris’s campaign was too “woke,” or that her failure to identify what she would’ve done differently to Biden was fatally damaging. Still others would point to record inflation and other economic pressures.

Although these theories stack up, none of them answer the real question here: How could a country with democratic values so deeply ingrained in its national ethos elect a president who openly defies them?

The truth is that democratic capitalism has been steadily building toward a foreseeable crisis for the last 45 years, comprising three mutually reinforcing trends that began during the Reagan era: Stagnating growth, rising inequality and growing polarization.

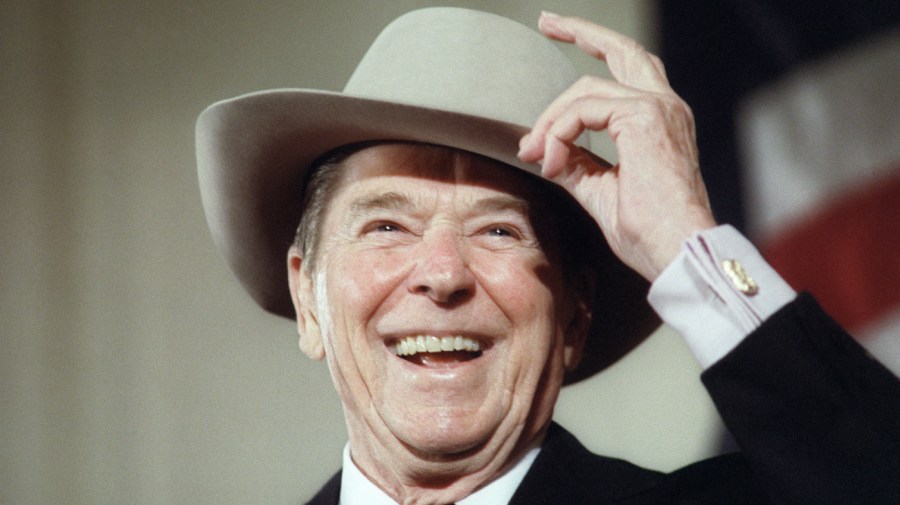

Sure, the Trump vs. Reagan comparison is overdone. But what’s overlooked is how Reagan’s policies created the conditions for a populist power grab. Reagan came to power at a time when the growth rate was the highest since the industrial revolution. Inequality was trending downward, and almost everyone was sharing the fruits of progress.

But the Reagan administration turned its back on the welfare model established by his predecessors, in favor of the political-economic theory and ideology of neo-liberalism. The neo-liberals rejected the idea that tax-funded government programs are the best way to improve lives. Rather, they believed that when the market prospers, everyone prospers. And the market prospers when the government stops standing in its way. Tax rates were cut dramatically for the wealthy, leading to a rapid rise in income inequality.

Since the introduction of so-called Reaganomics in the 1980s, the share of the top 1 percent and top 10 percent in income and wealth has been increasing dramatically at the expense of everyone else. This is a global trend, but it has been most stark in the U.S.

This was compounded by the information revolution, creating a huge skill premium (that is, the difference in wages between skilled and unskilled workers). Pair that shift to a service-based economy with increasing de-industrialization, and this exacerbated the already widening wealth disparity. Manufacturing bases across the Rust Belt had been or were being shuttered, which accelerated job losses for blue-collar workers. As a result, inequality is now nearing levels last seen in the roaring ’20s.

The 1980s also marked the end of the era of rapid growth. In the 1960s, the U.S. economy was growing on average by more than 4 percent per year. Over the last decade, that figure stands at roughly 2 percent. The implications of fast inequality growth and slow economic growth deeply hurt those below the breadline.

Slow growth prevents the economy from mitigating the effects of rising inequality. A slower-growing pie less equally divided led to a generation worse off than its parents.

In the 40 years leading up to Trump’s first election victory, real hourly wages for Americans without college degrees — 64 percent of the population — actually shrank. Wages for workers with high school degrees dipped from $19.25 to $18.57, while workers who didn’t complete high school experienced a decline from $15.50 to $13.66.

We see the effects of this sharply in the housing market; in 2016, the average worker needed to work 40 percent longer to afford a median house than he or she did in 1976.

This exposes a deep contradiction at the very heart of capitalist democracy. If inequality is rising and most people are worse off, how could the majority keep voting for parties and presidents that perpetuate a system that doesn’t serve them?

The answer lies in the third driving force: political polarization. Politicians resort to divisive electioneering tactics to motivate voters to vote against the other side. These are often framed as an ever-growing threat to the U.S.

The topics change: the war on terror, immigration, critical race theory and gender. But the strategy is the same. Distract from the key contradiction in the system — a democracy that serves mostly the elites — by focusing anger on other issues.

The result is a political culture of ever-growing polarization and radicalization on both the right and the left. This polarization allows for the entrance into the political sphere of extreme populist positions. It also creates an opportunity to exploit a divided political system with many voters who have lost faith in the establishment for an authoritarian power grab. Trump was the first person to seize that opportunity.

Truth be told, it is amazing that another “Donald Trump” didn’t happen sooner. All it would have taken is the right presidential candidate to come along during the 2008 Obama versus McCain presidential campaign. They’d just need to weaponize the conditions set in motion by in the ’80s — slow growth, increasing inequality and growing polarization. This is the recipe for Trump’s populist power grab, which has undermined the very foundations of U.S. democratic culture.

Gilad Tanay is founder and chairperson of ERI Institute, a research firm specializing in social impact and philanthropy.