“Kill two birds with one stone” — this is America Inc.’s proposition to the incoming Trump administration as it lobbies for a double-sided détente with Venezuela to help increase energy imports and halt migratory flows to the Southern border.

The oil industry and financiers with stakes in the Venezuelan economy see an opportunity to shift the Republicans away from the “maximum pressure” approach of President-elect Trump’s first term. This was premised on strict sanctions, aimed at forcing out President Nicolás Maduro, an authoritarian socialist.

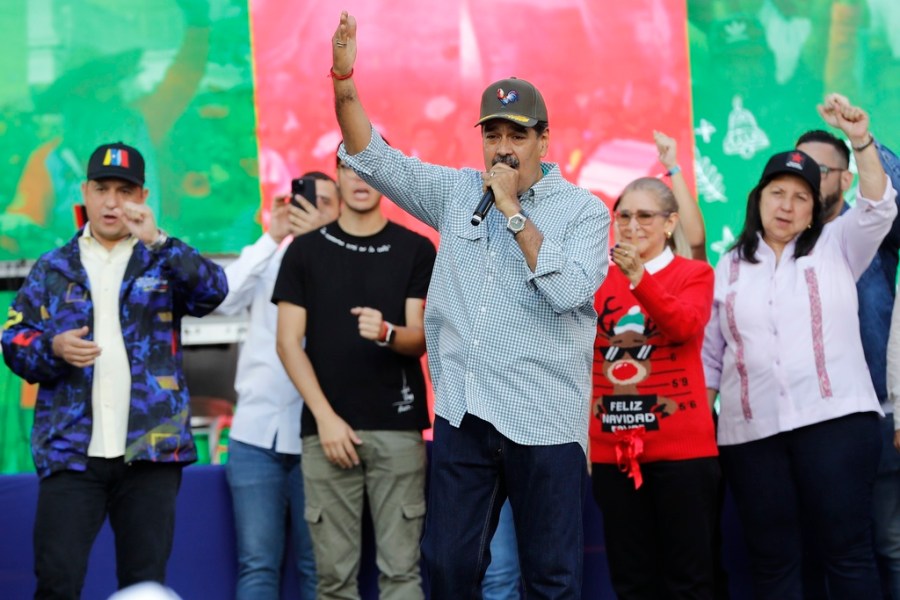

Maduro, who remains in post, will himself be inaugurated (for a third term) in January despite the firm international consensus that he lost July’s national elections to the opposition bloc.

Given Maduro’s longevity, Trump’s love of deals that put “America First,” and the realism of figures like Vice President-elect JD Vance, there is reason to believe that this new flavour of Republicanism will repudiate the policy of regime change.

An energy-migration pact is indeed emerging, premised on the un-freezing of sanctions on Venezuela’s world-leading energy reserves in return for Maduro stemming emigration and accepting the return of already departed migrants. Team Trump, beyond its skepticism of interventionist doctrine, should see this as a viable way to tick off two key Republican election commitments: cheaper gas and secure borders.

The current state of U.S.-Venezuela relations is wholly unsatisfactory. American sanctions have had their desired impact in crippling the Venezuelan economy, but the second order effects have been deleterious. More than 7.7 million migrants have fled Venezuela as of May 2024, and U.S. and European consumers alike remain mostly cut off from the largest proven oil reserves on earth.

Inflation, driven in good part by the recent energy supply crunch, has been a death knell to incumbent governments across the West. Along with inflation, it was voter perceptions of border chaos under the Biden administration that sunk Kamala Harris’ chances with swing voters. Arizona, on the frontline of the crisis, flipped back convincingly to the Republicans.

The U.S.’ loss, in terms of prices at the pump and border security, has been its rivals’ gain.

Venezuela has drifted into alignment with the anti-American bloc, cementing economic and military ties with China, Russia and Iran. The realist generation (Henry Kissinger et al) that preceded the liberal-interventionist consensus of the past 30 years, would never have allowed hostile powers to expand so readily in the Western Hemisphere.

Despite its failings, the Biden administration did at least consider a path to détente. Sanctions on Venezuela’s energy sector were temporarily frozen in October 2023 under the Barbados Agreement, only to be reimposed in April of this year.

Nonetheless, the U.S.’ Office of Foreign Assets Control has allowed a number of oil producers to restart production in Venezuela under the so-called Chevron Model. Chevron and others operate under joint venture agreements with Venezuela’s state oil company, which are overlaid by contracts that offer certainty of supply and protect against corrupt practices.

As a result, Venezuela’s energy exports are now at a four-year high. The expansion of private sector activity with the blessing of the U.S. government would greatly increase flows, helping to stabilize the Venezuelan economy. This would undercut the strong incentive for citizens to depart and never return.

From this foundation, the Trump administration should seek to negotiate the repatriation of Venezuelans already in the U.S. or situated on Mexico’s side of the border. Maduro might even be convinced to support the return of nationals from the U.S. to his left-wing allies, not least Colombia, Nicaragua and Honduras.

Such a deal would be a major diplomatic and economic coup for Trump — demonstrating a deftness of touch that has eluded President Biden — as well as constituting a rare boon for regional stability.

Current thinking says much will hinge on the attitude of Marco Rubio, Trump’s nominee for secretary of State. Rubio is a strong interventionist in the mould of Dick Cheney and John Bolton and has long targeted Maduro.

Nonetheless, Trump will call the shots on foreign policy and will expect complete loyalty from the State Department. Rubio is also as opposed to Chinese and Russian expansionism as he is to Latin American socialism. He may yet realize that pursuing regime change in Venezuela will only further embolden the U.S.’ core competitors.

The path is narrow, but myriad factors point to a change of direction in U.S.-Venezuela relations. Indeed, a détente on realist lines, based on mutual gains in energy and border security, is backed by powerful private sector forces as the cure to the current malaise.

If nothing changes, Venezuelan instability will remain an open wound in the Western Hemisphere. The president-elect would soon regret not acting swiftly to end the psychodrama in both sides’ interest.

Jose Chalhoub is an analyst at Jose Parejo & Associates and oil market expert.